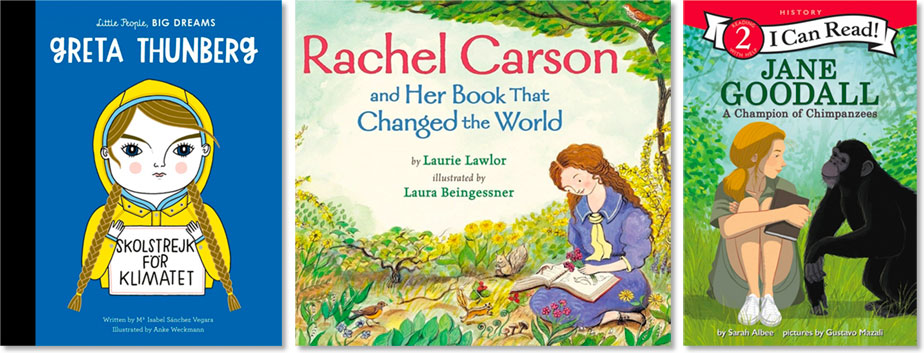

A Mighty Girl's top picks of books for children about trailblazing female environmentalists of the past and present.

With Earth Month comes a special opportunity to teach kids about the people all around the world doing important work to care for our environment and the life within it! In addition to the day-to-day activities that we can all do to reduce our impact on the planet, it's important to recognize the scientists and activists, both past and present, who have encouraged us to see our planet in a new way: not as a set of resources for us to extract when we please, but as a precious and delicate system that sustains all life that we must strive to protect. Continue reading Continue reading

With Earth Month comes a special opportunity to teach kids about the people all around the world doing important work to care for our environment and the life within it! In addition to the day-to-day activities that we can all do to reduce our impact on the planet, it's important to recognize the scientists and activists, both past and present, who have encouraged us to see our planet in a new way: not as a set of resources for us to extract when we please, but as a precious and delicate system that sustains all life that we must strive to protect. Continue reading Continue reading