16 Trailblazing Female Wartime Heroes Who Belong in the History Books

Often, the popular image of women in wartime is worried wives, girlfriends, sisters, and daughters, pining at home for the men they love who are risking their lives on the battlefield. The reality, though, is much different! Women have always made significant contributions to war efforts — both on the homefront and on the front lines. While women's contributions at home, especially during WWII, have become more widely known, the stories of their heroism on the battlefield are rarely told. In every war there have been women who dared to spy across enemy lines; treat wounded soldiers in the midst of the fighting; report from the front as journalists, and fight shoulder to shoulder with their male peers. And although we don't hear of them often, women also fought for an equally important cause: peace.

Often, the popular image of women in wartime is worried wives, girlfriends, sisters, and daughters, pining at home for the men they love who are risking their lives on the battlefield. The reality, though, is much different! Women have always made significant contributions to war efforts — both on the homefront and on the front lines. While women's contributions at home, especially during WWII, have become more widely known, the stories of their heroism on the battlefield are rarely told. In every war there have been women who dared to spy across enemy lines; treat wounded soldiers in the midst of the fighting; report from the front as journalists, and fight shoulder to shoulder with their male peers. And although we don't hear of them often, women also fought for an equally important cause: peace.

In this blog post, we're sharing stories of remarkable women from the Hundred Years' War to World War II. These women were spies, resisters, rescuers, medics, journalists, soldiers, and peacemakers; they risked as much and acted as bravely as their more renowned male counterparts. While a few of these figures were famous in their own times, their stories have faded in the years since, and most were little known or disregarded, even as they committed remarkable acts of heroism. Today, we can finally give them their due — and marvel at their incredible stories, which prove that truth is often far more exciting than fiction!

If you'd like to learn more about any of the featured women or introduce them to children and teens, after each profile we've shared several reading recommendations for both children and adults, as well as other resources that celebrate these remarkable women.

For more stories of inspiring women, check out the other two blog posts in our Mighty Girl Heroes blog series, Guardians of the Planet: 16 Women Environmentalists You Should Know and Those Who Dared to Discover: 16 Women Scientists You Should Know.

Women Heroes of Wartime

Joan of Arc (1412 - 1431)

Artist's interpretation of Joan of Arc, circa 1485

Artist's interpretation of Joan of Arc, circa 1485It's fitting that we start with one of the most famous female soldiers and war leaders of history. Jeanne (anglicized as Joan) was a French peasant girl who, as a young teen, said she saw visions of angels and saints urging her to support Charles VII in defeating the English in the ongoing Hundred Years' War. To everyone's surprise, the charismatic Joan also demonstrated strategic savvy and her participation in several swift victories gave a tremendous boost to the morale of the French forces. She was captured at Compiegne in 1430 and faced a poorly conducted, politically motivated trial; despite being uneducated, she defended herself with subtlety and wit, shocking those in attendance. She was convicted of heresy for "cross-dressing" — wearing male military garb and cutting her hair short — for which she was burned at the stake in 1431. However, in 1456, an inquisitorial court appointed by Pope Callixtus III declared her innocent and proclaimed her a martyr; she was canonized as a saint in 1920. To this day, this remarkable figure — an illiterate peasant girl who claimed to be on a mission from God and changed the course of history — remains a source of fascination and inspiration to many.

Sybil Ludington (1761 - 1839)

Statue of Sybil Ludington

Statue of Sybil LudingtonIt's a rare person who hasn't heard of Paul Revere and his "Midnight Ride," but did you know that, two years later, a 16-year-old girl named Sybil Ludington rode twice as far as Revere to muster her father's regiment against another British attack? On April 26, 1777, Ludington heard that the British forces were planning an attack on Danbury, Connecticut; she became determined to reach her father, Colonel Henry Ludington, so he could prepare his 400 militiamen to respond. She rode through soaking rain, alerting troops along her way, warning the people of Danbury, and even fighting off a highwayman with a stick as she rode. While her efforts could not stop the British from burning Danbury, Col. Ludington's troops were able to join forces with the Continental Army at the Battle of Ridgefield, forcing the British to return to their boats. Although Sybil Ludington was personally thanked by General George Washington for her efforts, it was Paul Revere who became a household name; it's only thanks to a written account from her great-grandson that the exciting tale of Sybil Ludington's ride has been preserved.

Florence Nightingale (1820 - 1910)

Florence Nightingale

Florence NightingaleWhen Florence Nightingale was born to a wealthy British family, it was expected that she would become a proper high society lady -- but she had other plans. She defied her parents' plans for marriage and instead, in 1854, she traveled to Scutari in the Ottoman Empire with 38 volunteer nurses that she had trained to treat the wounded soldiers of the Crimean War. Nightingale was appalled at the poor hygiene and lack of nutritious food that resulted in thousands of soldiers — ten times more than were wounded or killed in battle — dying of communicable diseases like typhoid, cholera, and dysentery. Nightingale became famous as "The Lady with the Lamp" who conducted rounds among the sick and wounded. Nightingale's ongoing legacy is her role founding the modern nursing profession and in using her statistical skills to show the importance of proper sanitation. However, to the troops under her care, she was forever remembered as what The Times called a "ministering angel" who "[w]hen all the medical officers have retired for the night... may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds."

Clara Barton (1821 - 1912)

Clara Barton

Clara BartonThis compassionate and dedicated nurse became famous as "the angel of the battlefield" for her willingness to go into combat to help wounded soldiers, rather than staying behind the lines. Clara Barton was a teacher when the American Civil War, and she immediately knew that she had to find a way to help. She spent the years of the war providing supplies and support to wounded soldiers, and after the war, helped establish a way to reunite missing men with their families. Her new path in life set, Barton traveled to Europe to assist with preparing military hospitals during the Franco-Prussian war. There, she discovered International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva and became determined to establish a similar organization dedicated to providing neutral humanitarian aid to Americans. Initially, there was little interest as few people believed that a conflict like the Civil War could ever happen within the nation's borders again; it took years of campaigning, as well as the argument that an American Red Cross could assist during natural disasters, before the American Association of the Red Cross was founded in 1881. Her courage stood as an example to nurses and other emergency medical personnel; she once said, "I may be compelled to face danger, but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them."

Harriet Tubman (1822 - 1913)

Harriet Tubman

Harriet TubmanThis near legendary abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor is nearly a household name but many people are surprised to learn that Harriet Tubman had a key role to play in wartime as well. When the Civil War broke out, Tubman saw a Union victory as a key element to ensuring the abolition of slavery throughout America. Tubman joined the Union forces and urged their officers to see escaped slaves not as "contraband" — seized by the Northern forces and put to work without pay — but as people who could aid their cause. She also offered her own expertise, starting as a nurse in Port Royal, South Carolina, and then working as a scout and spy for the Union forces, using the skills she had developed while smuggling people out of the South to smuggle information instead. She even became the first woman to lead an assault in the Civil War, by commanding the Combahee River raid that freed over 750 slaves. Her treatment after the war was over highlighted how much attitudes still needed to change: despite her key role, she wasn't given a Civil War pension until 1899. Throughout her life, though, she shrugged off the dangers she had faced with both the Underground Railroad and the Union army, saying "I can't die but once."

Mary Walker (1832 - 1919)

Mary Walker

Mary WalkerThe only woman to ever be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor was best known during her life as a feminist, abolitionist, surgeon... and the woman who insisted on wearing pants! Mary Edwards Walker was one of America's first female doctors, and eschewed the heavy dresses expected of women, writing that "The greatest sorrows from which women suffer to-day are those physical, moral, and mental ones, that are caused by their unhygienic manner of dressing!" Instead, her preferred garb was trousers under a knee-length jacket or dress. When the Civil War broke out, she quickly volunteered to provide medical care for the Union army. At first, she was only permitted to work as a nurse, but by 1863 she was officially contracted as a civilian surgeon — one who frequently crossed battle lines to assist the wounded, and who regularly treated civilians. She was captured by Confederate forces in 1864 and accused of being a spy, but later was freed as part of a prisoner exchange. President Andrew Johnson awarded her with the Medal of Honor in 1865. In her later life, she went on to argue for women's suffrage -- and for a cause close to her heart, dress reform.

Sarah Emma Edmonds (1841 - 1898)

Sarah Emma Edmonds

Sarah Emma EdmondsAt one point in Sarah Emma Edmonds' strange but true Civil War career, she was a woman, disguised as a man... disguised as a woman! The Canadian-born Edmonds fled an abusive father for the United States in her teens, and when the Civil War broke out, she felt impelled by patriotism to join the war effort. Inspired by a book, she disguised herself as a man and joined the 2nd Michigan Infantry as Franklin Flint Thompson, serving as a field nurse. But partway through the war, she started operating as a spy for the Union, disguising herself in a variety of ways, including as a black man or as laundry woman. "Frank Thompson's" career ended when she contracted malaria, since she didn't dare present herself at a hospital without her true identity being discovered, and she was given a dishonorable discharge for desertion. However, after publishing a best-selling account of her military experience, her desertion charge was dropped and she received a government pension for her military service. And in 1897, she became the only woman ever admitted to the Civil War veteran's organization The Grand Army of the Republic.

Jane Addams (1860 - 1935)

Jane Addams

Jane AddamsThis women's rights activist and pioneering social reformer, the first American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, was once considered "the most dangerous woman in the United States" for her dedication to diplomacy and pacifism. Jane Addams is considered the founder of the social work profession for co-founding Hull House, a settlement house providing education and health care to all, in 1889. Her work for peace began in earnest in 1915, when she was elected president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and helped organize the first significant international effort to mediate between the warring nations. Her dedication to pacifism resulted in severe criticism, and even charges that she was unpatriotic, once the US joined the war. After the war was over, however, she received support again, particularly for her ongoing efforts with the WILPF to ban poison gas. By the time she received the Nobel Prize in 1931, she was once again hailed as an example to the world. Her life stands as a testament to her own image of peace: "True peace is not merely the absence of war, it is the presence of justice."

Edith Cavell (1865 - 1915)

Edith Cavell

Edith CavellAlthough Edith Cavell didn't begin her nursing career until she was 30, her dedication to helping all those who needed her aid would bring her to a tragic end. The British woman quickly became renowned for her nursing skill, and in 1907 she was recruited to become the matron of a new nursing school in Brussels. When World War I broke out in 1914, biographer Diana Souhami says "[s]he told her nurses that they must not take sides in the conflict....Any wounded man must be medically treated; each was equal at the point of need." When the Germans invaded Brussels, she chose to stay, and continued to treat both German and Allied wounded alike. However, she could not ignore her support for the Allies, so she joined a network dedicated to smuggling wounded British and French soldiers to safety. When she was discovered, she was immediately arrested and sentenced to execution for treason. Although there were numerous international calls for mercy, Cavell was executed by firing squad on October 12, 1915. Cavell's execution was condemned worldwide and prompted a fierce will to win the war in Britain. She was viewed by many as a heroic martyr to the cause; one Allied journalist observed, "What Jeanne d’Arc has been for centuries to France that will Edith Cavell become to the future generations of Britons.” However, many consider her greatest legacy her push for the modernization of the nursing field which contributed to a change in the perception of nurses from kindly ladies sitting by bedsides to skilled medical professionals.

Josephine Baker (1906 - 1975)

Josephine Baker

Josephine BakerJosephine Baker is best known as a jazz singer, dancer, and actress -- but did you know she was also a World War II spy? The American celebrity was the first African American woman to integrate an American concert hall, but in France, she found both popular success and a welcoming environment, eventually making Paris her permanent home. Once the war broke out, she assisted the French government by gathering information when attending high society events at embassies; she also helped many people whose lives were threatened by the Nazis get visas to escape France. Once the Germans invaded France, she also used her unique position as a traveling artist to assist the Resistance: she visited neutral nations as part of her performance tours, smuggling secrets by writing them on her jazz sheet music in invisible ink. For her service, she received the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance, and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur; when she died, she was the first American-born woman to receive full French military honors at her funeral. Her remarkable show business career is well worth celebrating, but the grit and selflessness she demonstrated in wartime shows a different side of this larger-than-life woman.

Jacqueline Cochran (1906 - 1980)

Jacqueline Cochran

Jacqueline CochranIt only took one ride in an airplane to make aviation pioneer Jacqueline Cochran realize that she was destined to fly: she immediately started taking flying lessons and learned to fly solo in just three weeks. By the late 1930s she was nearly as well known as Amelia Earhart, but it was during World War II that Cochran had her most dramatic influence on aviation. She campaigned tirelessely for women pilots to have the opportunity to support the war effort by flying non-combat missions, such as delivering new aircraft and conducting reconnaissance. Cochran eventually became the director and a key trainer of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs); the WASPs proved that women pilots were equally competent -- and daring -- as their male counterparts. Under her direction, the WASP pilots flew 60 million miles of operational flights and delivered over 12,000 aircraft of 78 different varieties over two years. For her war efforts, she received the Distinguished Service Medal and the Distinguished Flying Cross. After the war, Cochran continued to make aviation history -- including becoming the first woman pilot to break the sound barrier -- and was involved with the Mercury 13 program to determine if women could be acceptable astronaut candidates. Sadly, she never lived to see an American woman go to space, and she always wished it could have been different: "I'd have given my right eye to be an astronaut."

Irena Sendler (1910 - 2008)

Irena Sendler

Irena SendlerOne of the great heroines of the World War II Warsaw Ghetto could have been forgotten if it weren't for a research project by several Kansas high school students. Irena Sendler was a Polish Catholic nurse and social worker in Warsaw who joined Zegota -- the underground Polish resistance organization created to aid the country's Jewish population -- after Germany invaded in 1939. Using her medical credentials to get access to the ghetto, Sendler and her colleagues set up a smuggling operation to get Jewish children out -- hiding in a false-bottomed ambulance, baskets, coffins, and even potato sacks -- give them false identities, and place them in orphanages and with Polish families. All the while, Sendler kept lists of the real names of the children, buried in jars to keep them safe. After rescuing over 2,500 children, Sendler was arrested, tortured, and sentenced to death; however, her friends in Zegota bribed her guards and she escaped to live in hiding for the remainder of the war. Although she was honored in the 1960s, including by Yad Vashem as one of the Polish Righteous among the Nations, by the 1990s her story had been almost completely forgotten -- until, in 1999, high school students Megan Steward, Elizabeth Cambers, and Sabrina Coons discovered a short news clipping about her, researched her life, and wrote a play that reignited widespread interest in this humble hero.

Nancy Wake (1912 - 2011)

Nancy Wake

Nancy WakeThe New Zealand-born British secret agent Nancy Wake has a story that's better than any spy film! After running away from home at 16 to become a nurse and a journalist, Wake traveled to New York, London, and Paris, then settled in Marseilles with her husband. When Germany invaded France, she immediately became a courier for the Resistance. By 1943, the Gestapo had nicknamed her the White Mouse for her ability to elude capture and declared her their most wanted person, with a five million franc bounty on her head. When the local resistance network was betrayed, Wake trekked across the country to escape to Britain through Spain -- but she wasn't done yet. She joined the Special Operations Executive and parachuted back into France in 1944 to help the Resistance prepare to assist in the Allied invasion. With her help, a group of 7,500 Resistance guerrillas successfully engaged with over 22,000 Nazi soldiers. After the war, Wake became the Allies' most decorated servicewoman and published her autobiography -- and she did become the subject of a made-for-TV movie in 1987. However, she didn't feel the portrayal did her justice, particularly scoffing at a scene of her cooking breakfast: "For goodness sake, did the Allies parachute me into France to fry eggs and bacon for the men?" she asked. "There wasn’t an egg to be had for love nor money, and even if there had been, why would I be frying it when I had men to do that sort of thing?"

Pearl Witherington (1914 - 2008)

Pearl Witherington

Pearl WitheringtonIn 1943, a British Special Operations Executive agent parachuted into occupied France. It sounds like the beginning of a spy movie, but it’s actually the real-life story of Pearl Witherington! Witherington was working at the British embassy in Paris when the Germans invaded; after she was evacuated, she was determined to help those she left behind. She joined the Special Operations Executive, where she was hailed as the best shot they service had ever seen, and quickly returned to France, eventually leading a resistance network under the code name Pauline. Her network was so effective that the Nazis put a one million franc bounty on her head. After the war, when Witherington was offered a British civil award, she declined, stating "there was nothing remotely 'civil' about what I did. I didn't sit behind a desk all day." She later received a military Member of the Order of the British Empire, as well as France’s Legion d’honneur. But she had never been motivated by the awards; instead, she wanted to protect her adopted homeland. "I just thought, This is impossible. Imagine that someone comes into your home - someone you don’t like -- he settles down, gives orders: 'Here we are, we’re at home now; you must obey.' To me that was unbearable."

Marguerite Higgins (1920 - 1966)

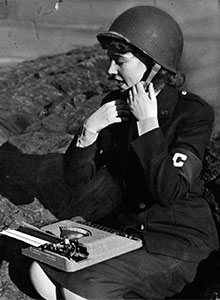

Marguerite Higgins

Marguerite HigginsWhen Marguerite Higgins was featured in Life magazine, the headline was "Girl War Correspondent" -- but she was so much more than the title implies. The daring American journalist convinced the New York Herald Tribune to send her to Europe in 1944, only two years into her career. She ended up covering the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp and the trials at Nuremberg. When the Korean war began, she was one of the first reporters to arrive, but she was ordered out of the country on the grounds that women did not belong at the front. Higgins appealed to General Douglas MacArthur, who replied with a telegram to the Herald Tribune: "Ban on women correspondents in Korea has been lifted. Marguerite Higgins is held in highest professional esteem by everyone." This decision, along with her shared Pulitzer Prize win for International Reporting in 1951, were major breakthroughs for women reporters. She went on to cover the Vietnam War and work as a syndicated columnist for Newsday. Her spirit is best summed up by her response when she was ordered out of Korea: "I wouldn't be here if there were no trouble. Trouble is news, and the gathering of news is my job."

Sophie Scholl (1921 - 1943)

Sophie Scholl

Sophie SchollPerhaps the bravest heroes of all are those who realize the dangerous path that their country is walking -- and stand up against it. As a university student in Munich, Scholl became involved in resistance organizing after learning of the mass killings of Jews and reading an anti-Nazi sermon by Clemens August Graf von Galen, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Münster. She was deeply moved by the "theology of conscience" and joined with her brother Hans and several friends to start a resistance movement called the White Rose, where she helped print and distribute anti-Nazi leaflets. In 1943 she was arrested by the Gestapo for treason, and after a short show trial on February 22, she was executed within hours of being sentenced to death. She stands as an example of the power -- and the need -- for individuals to stand up for what is right, even in the face of great risks. In her final statement, just before her execution by guillotine, the 21-year-old activist said, "How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause. Such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go, but what does my death matter, if through us thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?"