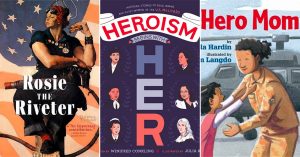

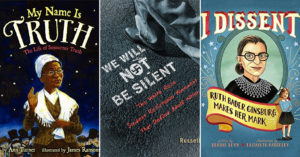

From soldiers to spies to peacemakers, these remarkable women made tremendous contributions during "The Great War."

On the "eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month" in 1918, World War I finally came to an end after four devastating years. The day of the armistice became a national holiday in many countries, a solemn day to remember the nine million soldiers and the seven million civilians who died during the Great War which was deemed, at the time, the "war to end all wars." When stories are told of wartime heroism, most focus on the brave men who fought in the trenches along the front lines, but heroes played many roles during those long years of war.

On the "eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month" in 1918, World War I finally came to an end after four devastating years. The day of the armistice became a national holiday in many countries, a solemn day to remember the nine million soldiers and the seven million civilians who died during the Great War which was deemed, at the time, the "war to end all wars." When stories are told of wartime heroism, most focus on the brave men who fought in the trenches along the front lines, but heroes played many roles during those long years of war.

Since women were not usually allowed in military service at the time, their important contributions to the war effort have too often been neglected in history books. To remedy this, in this blog post, we're introducing nine remarkable women who deserve broader recognition for their efforts ranging from smuggling wounded soldiers to safety, spying for the Allies, establishing hospitals, and negotiating for peace. May their heroic work be remembered, and serve as a reminder of the horrors of war and the necessity of ensuring that a world-wide conflict never occurs again.

Women of World War I That You Should Know

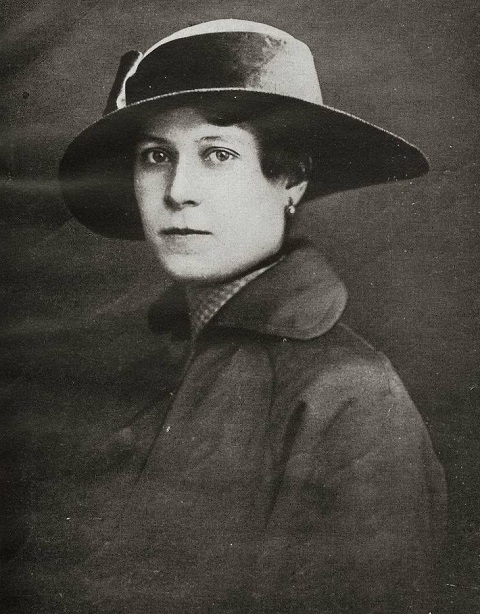

Jane Addams (1860 - 1935)

This women's rights activist and pioneering social reformer, the first American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, was once considered "the most dangerous woman in the United States" because of her dedication to peace and diplomacy. Jane Addams, who is also known as the founder of social work, co-founded Chicago's Hull House, the most famous settlement house in America, in 1889. After the outbreak of WWI, she was elected the national chair of the Woman's Peace Party president and presided over a meeting of 1,200 peace activists from 12 nations at The Hague in 1915. Addams, pictured at right, helped organize the first significant international effort to mediate between the warring nations, and she visited leaders of multiple European nations, urging them to sign a non-aggression pact and put an end to the war. Her dedication to peace earned her severe criticism in the midst of the Great War's nationalism, and even charges that she was unpatriotic once the US joined the war. After the war was over, however, people began to support her again — particularly for her efforts with the newly formed Women's International League for Peace and Freedom to ban the poison gases whose horrors had been revealed during WWI — and by the time she received the Nobel Prize in 1931, she was once again hailed as an example to the world. Her life stands as a testament to her own image of peace: "True peace is not merely the absence of war, it is the presence of justice."

Grace Banker (1892 - 1966)

Near the battlefields of France — often with shells falling all around her — American telephone operator Grace Banker led a group of 33 women who connected critical calls between Allied forces: they were the first group of U.S Army Signal Corps Telephone Girls, also known as the Hello Girls. Communications between Allied forces were dependent on a battle-rigged telephone system, but local operators were rarely fluent in English. U.S. General John Pershing put out a call for multilingual women to become "switchboard soldiers," and Banker, who worked at AT&T as a switchboard instructor, was one of the first selected. With her Telephone Unit No. 1, Banker operated the switchboards while under artillery bombardment and being bombed by German planes during the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Offensives. At the height of the war, the Hello Girls were connecting 150,000 calls a day; in total, 223 American women served in this critical role over the course of the war. After the war, Banker was given a Distinguished Service Medal, but even though she and the other Hello Girls swore the Army oath and were subject to military discipline, the Department of War denied them veterans' status and benefits. It wasn't until 1977, after decades of petitioning presidents, that the Hello Girls were finally given their due and recognized for their service as veterans.

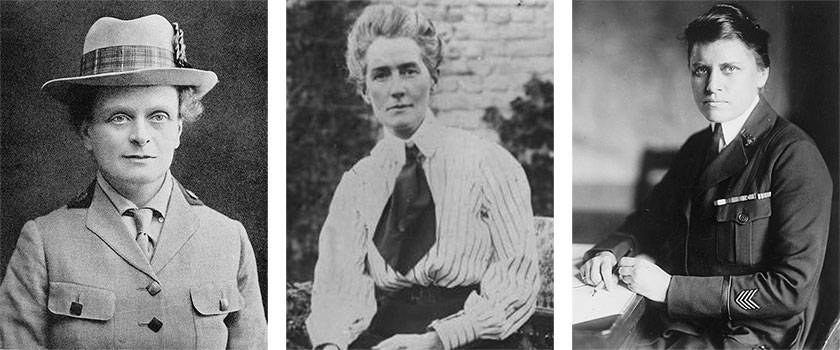

Edith Cavell (1865 - 1915)

Although Edith Cavell didn't begin her nursing career until she was 30, her dedication to helping all those who needed her aid would bring her to a tragic end. The British woman quickly became renowned for her nursing skill, and in 1907 she was recruited to become the matron of a new nursing school in Brussels. When World War I broke out in 1914, biographer Diana Souhami says "[s]he told her nurses that they must not take sides in the conflict....Any wounded man must be medically treated; each was equal at the point of need." When the Germans invaded Brussels, she chose to stay, and continued to treat both German and Allied wounded alike. However, she could not ignore her support for the Allies, so she joined a network dedicated to smuggling wounded British and French soldiers to safety. When she was discovered, she was immediately arrested and sentenced to execution for treason. Although there were numerous international calls for mercy, Cavell was executed by firing squad on October 12, 1915. Cavell's execution was condemned worldwide and prompted a fierce will to win the war in Britain. She was viewed by many as a heroic martyr to the cause; one Allied journalist observed, "What Jeanne d’Arc has been for centuries to France that will Edith Cavell become to the future generations of Britons.” However, many consider her greatest legacy her push for the modernization of the nursing field which contributed to a change in the perception of nurses from kindly ladies sitting by bedsides to skilled medical professionals.

Marthe Cnockaert (1892 - 1966)

In World War I Belgium, a young nurse quietly worked away... gathering intelligence for the Allies. Marthe Cnockaert saw the violence of war early; German troops invaded her village and burned her home in August 1914. She used her nursing training to get a job at a German-run hospital, even receiving an Iron Cross from Germany for her service. But in 1915, she was approached by Lucelle Deldonck, a family friend and British intelligence agent, who wanted to recruit her for an Anglo-Belgian spy network. Cnockaert's work as a nurse and as a waitress in her parents' cafe brought her into close contact with German military personnel, and her fluency in multiple languages made it easy for her to collect information, then relay it through the network. She also engaged in sabotage, but one effort resulted in her arrest: she lost her engraved watch as she was planting dynamite in an abandoned tunnel under a German ammunition depot, allowing authorities to identify her. She was sentenced to death for espionage, but her sentence was commuted to life in prison because of her earlier Iron Cross honor. After the war, she not only wrote a memoir about her work as a spy, but also multiple spy novels. "Because I am a woman I could not serve my country as a soldier," she wrote in her memoir. "I took the only course open to me."

Elsie Inglis (1864 - 1917)

Scottish doctor Elsie Inglis was instrumental in treating wartime epidemics — and in changing attitudes towards women in medicine. Inglis had been operating her own practice for twenty years when World War I broke out. The dedicated suffragist had already been toying with the idea of hospitals staffed by women, so she contacted the War Office offering a ready-made women-only unit for the war effort; in response, she was told "My good lady, go home and sit still." Undaunted, she founded the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Services (SWH), quickly raising substantial funds. The French government took advantage of her expertise, offering her what was supposed to be a 100-bed hospital in the Abbey of Royaumont; it soon swelled to over 600 as injuries from the Somme poured in. Inglis went with another unit to Serbia, where an epidemic of typhus had killed 16% of the population, and she and her team set to work. In 1915, she was captured and briefly held until US diplomats secured her release; whereupon, she left for Odessa, Russia to set up a SWH team there. Sadly, she was diagnosed with cancer in 1916 and died soon after, so she didn't see the over 1,000 women who saved hundreds of thousands of lives working for the 14 SWH medical teams operating in seven countries. The day before she died, she said to her niece, "It will be grand to start a new job over there, although there are two or three jobs I should like to have finished here first."

Flora Sandes (1876 - 1956)

The youngest, convention-defying daughter of an Irish family, Flores Sandes was the only British woman to serve as a soldier in World War I. Sandes grew up loving activities like horseback riding and shooting. When World War I began, she traveled to Serbia and joined the Red Cross, but when a Serbian soldier saw her ride, he said she should enlist as a soldier, not a nurse. She was delighted, telling a friend, "I've always wished to be a soldier and to fight." She became a private in 1915, but the following year, she was severely injured by a grenade; "I caught the little sergeant who had helped carry me watching me with his eyes full of tears," she remembered later. "I assured him that it took a lot to kill me, and that I should be back again in about ten days." She received the highest decoration of the Serbian Military and promoted to the rank of Sergeant major, but her injury prevented her from returning to battle and she spent the rest of the war running a hospital. At the end of the war, in recognition of her service, she was commissioned as an officer, making her the Serbian army's first female officer. For the rest of her life, Sandes reminisced about the freedom of her war experience. "I felt neither fish nor flesh when I came out of the army," she once said. "For seven years I lived practically a man's life."

Julia Catherine Stimson (1881 - 1948)

American nurse Julia Catherine Stimson devoted her military service to saving as many lives as she could — and she became the first woman to achieve the rank of major in the U.S. Army. Stimson wanted to be a doctor, but her parents encouraged her to consider nursing instead. When America entered the war in 1917, Stimson joined the Army Nurse Corps, becoming chief nurse for Base Hospital 21. In 1918, she became head of the Red Cross Nursing Service and later chief nurse of the American Expeditionary Forces, supervising 10,000 nurses. For her service, she was awarded the United States' Distinguished Service Medal and Britain's Royal Red Cross. Following the war and her promotion to major, Stimson became the superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps and the first dean of the Army School of Nursing. Although she was officially retired when World War II broke out, she was recalled to active duty to assist with recruiting; her additional service meant that she was promoted to full colonel shortly before her death. Today, Stimson is remembered for being one of the pioneering leaders who brought nursing to the status of a profession. Her spirit of daring no doubt encouraged many of the women who came after her: "Don't you worry about me one least little bit," she wrote to her family from the ship taking her to France. "I am having the time of my life and wouldn't have missed it for anything in the world."

Julia Hunt Catlin Park DePew Taufflieb (1864 - 1947)

When you hear the word "socialite" you might think of someone frivolous, but American socialite Julia Hunt Catlin Park DePew Taufflieb inspired an entire country's generosity with her work during World War I. After the death of her first husband, she moved to France, where she bought a country home, Chateau d'Annel. When the war broke out, it wasn't long before the Chateau was close to the front line — and Park DePew Taufflieb converted her home into a 300-bed hospital for the Allies, funding it all with her own money. Her actions inspired many other wealthy Americans living in France to open their own military hospitals. She also used her connections in the United States to quickly fundraise the equivalent of $85,000 today to help her support the 1,500 refugees living nearby, largely women and children. Park DePew Taufflieb ran the hospital for four years, often while under fire, before the German advance forced her to flee. For her service, she received France's highest military award, the Legion d'honneur, and the Croix de Guerre — the first American woman to receive either award.

Louise Thuliez (1881 - 1966)

Louise Thuliez was a French teacher who stumbled into working for the resistance when her village of Saint-Waast-la Vallée was invaded during World War I. Thuliez helped several wounded British soldiers who had been left behind in the evacuation make their way to a safe house, her first encounter with the resistance. By early 1915, Thuliez was busily escorting soldiers to a nursing home run by Edith Cavell, with whom she worked closely, so they could travel to safety. However, when the Germans increased surveillance that July, she was arrested along with Cavell. Like Cavell, Thuliez was sentenced to death, but Thuliez's sentence was commuted to life in prison after international outcry. She spent the rest of the war in a prison, suffering miserable conditions (and engaging in small acts of rebellion, like sewing buttons on military uniforms loosely so they would fall off.) After the war, Thuliez received the Legion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre, and wrote her autobiography. During World War II, she returned to her resistance work, helping Allied soldiers escape from occupied France. When asked why she took such risks, she gave the same answer she gave at her trial: “Because I am a French-woman.”