In honor of Banned Books Week, we're showcasing a selection of high quality books for children and teens that have been challenged or banned.

The Diary of A Young Girl is a classic Mighty Girl book that beautifully captures the emotional life of its author, Anne Frank, as her family and friends attempted to hide from the Nazi regime. It has been translated into 67 languages and sold over 30 million copies, and is often used by schools for units on the Holocaust or to discuss the feelings and physical changes that come with adolescence.

The Diary of A Young Girl is a classic Mighty Girl book that beautifully captures the emotional life of its author, Anne Frank, as her family and friends attempted to hide from the Nazi regime. It has been translated into 67 languages and sold over 30 million copies, and is often used by schools for units on the Holocaust or to discuss the feelings and physical changes that come with adolescence.

And yet, as recently as 2015, parents have challenged the use of the book in classrooms due to a reference to Anne's sexual awakening. In fact, since 1952, when the diary was first published in the US, it has been challenged dozens of times for reasons ranging from Anne’s discussion of her sexuality, to concerns about introducing the Holocaust to middle-school students, to disapproval of Anne’s unflattering descriptions of her mother. As the history of challenges to this book makes clear, one person’s bad influence is another person’s literary classic.

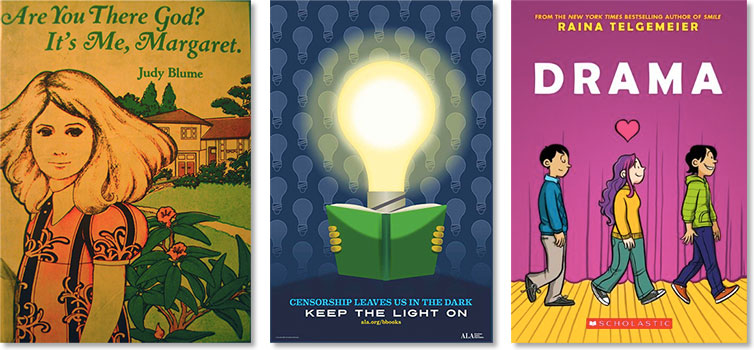

September 22 to 28 is Banned Books Week, “an annual event celebrating the freedom to read…[and] to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.” During this week, The American Library Association and others in the book community come together to expose the dangers of restricting access to books. The banning of books, at least in the US, occurs on a local level, generally by local school districts which decide to pull a book from school libraries or classrooms. Often a book that is banned in one school district is a core part of the curriculum in many others.

September 22 to 28 is Banned Books Week, “an annual event celebrating the freedom to read…[and] to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.” During this week, The American Library Association and others in the book community come together to expose the dangers of restricting access to books. The banning of books, at least in the US, occurs on a local level, generally by local school districts which decide to pull a book from school libraries or classrooms. Often a book that is banned in one school district is a core part of the curriculum in many others.

Banned Books Week celebrates that the majority of the books that have been challenged are still available on shelves, a testament to “the efforts of librarians, teachers, students, and community members who stand up and speak out for the freedom to read.”

At A Mighty Girl, we believe that children — and their parents — should be free to explore difficult ideas and concepts. While parents should be aware of potential concerns with a title, removing a book from the shelves limits choice and sends the message to children that they aren’t competent to handle challenging topics. With that in mind, we have gathered a selection of Mighty Girl books that have been challenged or banned. Many of these books are considered classics, and many have received literary awards. Yet for reasons ranging from racism to violence to religious objections, people have had to fight to keep these books accessible to readers. A Mighty Girl is proud to have each one as part of our collection of empowering titles.

Of course, there are many more books that have faced challenges or bans. For more comprehensive lists of all books, for both adults and children, that are frequently challenged, please see the ALA’s frequently challenged books page.

Mighty Girl Banned Books

When it comes to children’s books, the most common cause given for challenging a title is “inappropriate for age group” — in other words, objectors feel that the book addresses ideas that shouldn’t be introduced until children are older than the recommended age. A Mighty Girl believes that most topics can be introduced even to the youngest age groups, provided it is done with care and that parents or teachers help children discuss their reactions to these concepts. In fact, nearly every book on this list has also been challenged for being inappropriate for its recommended age.

![9780064402019[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/97800644020191-201x300.jpg) Another common “blanket” challenge is for “problematic material.” This doesn’t refer to specific concerns like racism, sexuality, or violence, but very subjective ideas of what constitutes a bad influence in literature. A good example of this is The Great Gilly Hopkins by Katherine Paterson (age 9 -12). Gilly is an eleven-year-old who has bounced from foster home to foster home for years; when she is placed with the Trotters, she’s determined to finally entice her biological mother to reclaim her. But when she finally ends up face-to-face with her “real” mother, Gilly realizes that her mother doesn’t want her back — and that perhaps life with the Trotters is the best thing that’s ever happened to her. Although Paterson won multiple awards for this novel, including a Newbery Honor and a National Book Award, The Great Gilly Hopkins is often challenged for supposedly glamorizing Gilly’s unpleasant behavior and for its negative depiction of a biological parent.

Another common “blanket” challenge is for “problematic material.” This doesn’t refer to specific concerns like racism, sexuality, or violence, but very subjective ideas of what constitutes a bad influence in literature. A good example of this is The Great Gilly Hopkins by Katherine Paterson (age 9 -12). Gilly is an eleven-year-old who has bounced from foster home to foster home for years; when she is placed with the Trotters, she’s determined to finally entice her biological mother to reclaim her. But when she finally ends up face-to-face with her “real” mother, Gilly realizes that her mother doesn’t want her back — and that perhaps life with the Trotters is the best thing that’s ever happened to her. Although Paterson won multiple awards for this novel, including a Newbery Honor and a National Book Award, The Great Gilly Hopkins is often challenged for supposedly glamorizing Gilly’s unpleasant behavior and for its negative depiction of a biological parent.

Lois Lowry’s Anastasia Krupnik (age 8 - 12) depicts a tumultuous year in a ten-year-old’s life: her teacher doesn’t understand her avant-garde poetry writing, she has a crush on a boy who doesn’t know she exists, and her embarrassing parents announce that they’re having a baby! Fortunately, as the year goes on — and she vents her feelings into her secret notebook — she realizes that things aren’t so bad after all. But because there are references to beer and Playboy magazine, and because of Anastasia’s rudeness to her parents and teachers, this book is also often declared inappropriate for tweens.

"Vulgarity" is another common reason given for a ban. Angie Thomas' The Hate U Give (age 15 and up) has been challenged by parents in some districts for being "pervasively vulgar" and for its depictions of drug use. However, as written in a post on the blog of the American Library Association's Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF), "profane language is not atypical in teen novels... the language and content of these books often mirror real-world behaviors." Moreover, they continue, the biggest problem with these challenges is that "an objection from a parent... [results in the book being withdrawn] not only for his child but for every single child in the district," whether or not other parents have issues with the title.

Too Scary: Books Banned for Violent Content

Most challenges and proposed bans are related to particular sensitive issues: racism, violence, religion, or sexuality. Violence is the most obvious one; many people are concerned about children reading about violent situations. Others counter that they would rather violence be presented in an unpleasant, true-to-life way, rather than being glamorized or minimized.

![616030-hungergames[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/616030-hungergames1-198x300.jpg) In the Newbery Medal-winning Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George (age 10 and up), 13- year-old orphan Miyax has a double life: although she was raised with traditional Inupiat teachings and is living in an arranged marriage, she is also known as Julie, the Americanized, educated girl who challenges tradition. After an assault by her arranged husband, Julie decides to run away to join her penpal in California, but travelling on her own through the Alaskan wilds gives her a new appreciation for Inupiat skills. The sexual assault scene — in which Julie’s husband forcefully kisses her and tears her clothing — is not graphically described but is the source of the majority of challenges to this book. George, however, has said that it is important that the reader understand just how unsafe Miyax/Julie felt to make her decision to run away alone plausible.

In the Newbery Medal-winning Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George (age 10 and up), 13- year-old orphan Miyax has a double life: although she was raised with traditional Inupiat teachings and is living in an arranged marriage, she is also known as Julie, the Americanized, educated girl who challenges tradition. After an assault by her arranged husband, Julie decides to run away to join her penpal in California, but travelling on her own through the Alaskan wilds gives her a new appreciation for Inupiat skills. The sexual assault scene — in which Julie’s husband forcefully kisses her and tears her clothing — is not graphically described but is the source of the majority of challenges to this book. George, however, has said that it is important that the reader understand just how unsafe Miyax/Julie felt to make her decision to run away alone plausible.

Unsurprisingly, Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy, made up of The Hunger Games, Catching Fire, and Mockingjay (all age 12 and up) are high on the list of recent books banned for violence. The story of Katniss Everdeen, who goes from rescuing her sister from a fight-to-the-death competition staged annually to amuse the decadent Capital; to becoming a symbol of revolution against the Capital by the populace and the mysterious District 13; and finally to a horrifying realization of what the revolution is willing to sacrifice in order to win, could not be told without shining a harsh light on the truth of what violent revolution is like. But Collins’ inspiration for the trilogy — flipping back and forth between reality TV with its voyeurism and social viciousness, and news networks with their simultaneously brutal and glorifying coverage of war — opens the question of whether hiding the realities of violent conflict and war is really what’s best for our children.

Prejudiced: Books Banned for Racism

![EWB09110366[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/EWB091103661-185x300.jpg) Racism is another theme that many people consider difficult for children, and debate rages about when it’s appropriate to teach children about racial discrimination and conflict. And even if the overall message of the book is equality and justice, books can still be challenged for racist actions or language. The classic Harper Lee novel To Kill A Mockingbird (age 12 and up) has been challenged many times, despite its message of justice and standing up for what is right. Through the eyes of Scout Finch, the story follows three years of her coming of age, punctuated by the arrest of a black man for allegedly raping a white woman and her father’s efforts to defend him.

Racism is another theme that many people consider difficult for children, and debate rages about when it’s appropriate to teach children about racial discrimination and conflict. And even if the overall message of the book is equality and justice, books can still be challenged for racist actions or language. The classic Harper Lee novel To Kill A Mockingbird (age 12 and up) has been challenged many times, despite its message of justice and standing up for what is right. Through the eyes of Scout Finch, the story follows three years of her coming of age, punctuated by the arrest of a black man for allegedly raping a white woman and her father’s efforts to defend him.

Although the novel was a cutting indictment of racism — particularly in the justice system — when it was written, more recently it has been criticized for not portraying the racism in its setting town of Maycomb negatively enough; critics also argue that the African American characters are stereotypically superstitious and eager to please. Many parents also object to the use of racial slurs in the novel. However, many fans of the book argue that the novel’s frank discussion of racial prejudice played a part in making the general population more aware of the need for social change, as well as civil rights legislation, in the decades after it was published.

![roll-of-thunder[2]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/roll-of-thunder2-225x300.jpg) The Newbery Medal-winning Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor (age 10 and up) is often attacked for its racist language. It tells the story of 9-year-old Cassie Logan, who has been protected by her family from the brutal racism of the 1930s Deep South. But when night riders start attacking African Americans, Cassie’s eyes are opened, and she has to deal with the bewilderment of realizing how many people will judge her by her race and learn how to steel herself against them. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry is also challenged because of the violence depicted, but the majority of challenges have to do with the racial issues raised by the book, since some parents argue that middle-schoolers are too young to understand the material.

The Newbery Medal-winning Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor (age 10 and up) is often attacked for its racist language. It tells the story of 9-year-old Cassie Logan, who has been protected by her family from the brutal racism of the 1930s Deep South. But when night riders start attacking African Americans, Cassie’s eyes are opened, and she has to deal with the bewilderment of realizing how many people will judge her by her race and learn how to steel herself against them. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry is also challenged because of the violence depicted, but the majority of challenges have to do with the racial issues raised by the book, since some parents argue that middle-schoolers are too young to understand the material.

Even autobiographical books for older teens are sometimes attacked for discussing racial issues. Dr. Maya Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (age 15 and up) is the first of multiple volumes of her life story. Following her parents’ separation, Angelou and her brother are sent to live with their grandmother, where their homesickness is compounded by racial prejudice from neighbors. After returning to her mother’s home, 8 -year-old Angelou is raped by her mother’s boyfriend, and has to live through the consequences and still find an identity and future that makes her proud of who she is. Angelou wrote the book as a combination of autobiography and novel, so she uses her experience of rape as a metaphor for the suffering of African Americans under overt and subtle prejudice. Unsurprisingly, in addition to the challenges related to the racial issues this book raises, protesters also object to the sexually explicit scenes (including, but not limited to, her description of her rape) and to what many consider to be unflattering depictions of institutionalized religion.

Irreverent: Books Banned due to Religious Objections

![htmlimport_goldencompass[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/htmlimport_goldencompass1-204x300.jpg) Religious objections are a frequent source of challenges to books, especially when the content of the book directly tackles problematic religious institutions. Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass (age 10 and up) tells the story of Lyra Bellacqua, who lives in an alternate world where everyone has a personal daemon, an external manifestation of their soul.

Religious objections are a frequent source of challenges to books, especially when the content of the book directly tackles problematic religious institutions. Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass (age 10 and up) tells the story of Lyra Bellacqua, who lives in an alternate world where everyone has a personal daemon, an external manifestation of their soul.

Lyra and her daemon Pan become the center of an adventure that begins with foiling her uncle’s assassination, and proceeds to unveil truths about her family, the disappearances of children she knows, and the role she is destined to play in saving her own world and others. One of Lyra’s major opponents, the Church, is presented as manipulative and power-hungry rather than faithful, leading to parents and religious organizations demanding its removal from shelves. Pullman, however, has made it clear that his objection is not to faith, but to the abuses committed in the name of faith: “throughout human history, the greatest moral advances have been made by religious leaders such as Jesus and the Buddha. And the greatest moral wickedness has been perpetrated by their followers.”

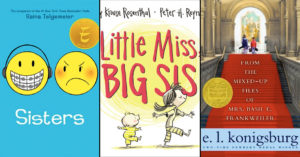

![Nasreens-Secret-School-800x987[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Nasreens-Secret-School-800x9871-243x300.jpg) Religious objections can even arise if the main character’s relationship with God or the divine are present, but different than expected. In Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (age 9 - 13), Margaret is the daughter of a Christian mother and a Jewish father — but her spiritual life is conducted on her own, in direct conversation with God, rather than through religious worship. And as she goes through the tumultuous time when she gets her period, deals with her changing body and feelings, and struggles to find her place among her friends, it’s this personal God that she talks to about everything. Objectors often consider this book immoral or irreverent because of its unusual take on faith; it’s also often subjected to complaints about the sexuality discussed in the plot.

Religious objections can even arise if the main character’s relationship with God or the divine are present, but different than expected. In Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (age 9 - 13), Margaret is the daughter of a Christian mother and a Jewish father — but her spiritual life is conducted on her own, in direct conversation with God, rather than through religious worship. And as she goes through the tumultuous time when she gets her period, deals with her changing body and feelings, and struggles to find her place among her friends, it’s this personal God that she talks to about everything. Objectors often consider this book immoral or irreverent because of its unusual take on faith; it’s also often subjected to complaints about the sexuality discussed in the plot.

There has also been a rise in people challenging a book simply for featuring a religion other than their own. Nasreen's Secret School by Jeannette Winter (age 7 - 9) appeared on the ALA's list of the 10 most challenged titles of 2015 after 6 years of publication. The book, which is based on a true story from Afghanistan, features a young Muslim girl, traumatized by the death of her parents, who gains new hope for the future after having an opportunity to learn to read. While some challengers cited the violence as being inappropriate, especially for the targeted age group, the most common reason cited was "religious viewpoint," namely that it promotes a religion other than Christianity. Similar complaints were leveled against Winter's book The Librarian of Basra, because of the belief that it promotes another religion besides Christianity.

Too Sexy: Books Banned for Sexuality

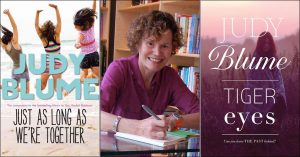

![deenie[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/deenie1-200x300.jpg) In fact, since many of her books deal with coming of age and puberty, Judy Blume is no stranger to challenges to her books based on sexuality, another major source of book protests. Whether it’s Margaret’s discussion with God about crushes, kissing, and sneaking a peek at Playboy, Deenie’s (12 and up) references to masturbation, or Forever’s (14 and up) frank talk about the choice to engage in sexual activity for the first time, Blume’s books are regularly the target of complaints that her books contain sexual references that are inappropriate for teens. Blume argues that, increasingly, parents “want to believe that if their children don't read about it, their children won't know about it. And if they don't know about it, it won't happen.” However, she believes that it’s critical for both boys and girls to understand their sexual development, which is why she says, “I wish the censors could read the letters kids write.”

In fact, since many of her books deal with coming of age and puberty, Judy Blume is no stranger to challenges to her books based on sexuality, another major source of book protests. Whether it’s Margaret’s discussion with God about crushes, kissing, and sneaking a peek at Playboy, Deenie’s (12 and up) references to masturbation, or Forever’s (14 and up) frank talk about the choice to engage in sexual activity for the first time, Blume’s books are regularly the target of complaints that her books contain sexual references that are inappropriate for teens. Blume argues that, increasingly, parents “want to believe that if their children don't read about it, their children won't know about it. And if they don't know about it, it won't happen.” However, she believes that it’s critical for both boys and girls to understand their sexual development, which is why she says, “I wish the censors could read the letters kids write.”

Stories that explore romantic and sexual relationships are often criticized and challenged by parents who believe that tweens and teens shouldn't be reading about sex — but if sexuality causes concern in a text novel, in a graphic novel it elicits even more dramatic responses. Kim Dong Hwa’s The Color of Earth manhwa graphic novel (age 10 and up) tells the story of Ehwa, who is coming of age in a quiet country village where her mother is low status because she is a single parent. As Ehwa grows, she not only explores romance herself, but also watches her mother find happiness with a traveling salesman. Editor Callista Brill says “We knew we were risking challenge when we published these books," especially since there are several depictions of both male and female nudity. "But sexuality is a part of the adolescent experience, and The Color of Earth and its sequels handle this conversation with remarkable honesty and positivity.”

![510-enmudsl[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/510-enmudsl1-206x300.jpg) Challenges fly faster when a book addresses the challenges facing the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) community. The groundbreaking book Annie On My Mind by Nancy Garden (age 13 and up) was the first to portray a lesbian relationship in a positive light, with a happy ending. The story of how Liza and Annie’s friendship evolves into love is genuine, and the chaos that erupts when their relationship is revealed is still familiar, despite the book being more than thirty years old. Not only has the book been frequently challenged, but in one infamous incident in 1993, copies of the book were actually burned in protest. When she was told, Garden responded, “Burned! I didn't think people burned books any more.”

Challenges fly faster when a book addresses the challenges facing the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) community. The groundbreaking book Annie On My Mind by Nancy Garden (age 13 and up) was the first to portray a lesbian relationship in a positive light, with a happy ending. The story of how Liza and Annie’s friendship evolves into love is genuine, and the chaos that erupts when their relationship is revealed is still familiar, despite the book being more than thirty years old. Not only has the book been frequently challenged, but in one infamous incident in 1993, copies of the book were actually burned in protest. When she was told, Garden responded, “Burned! I didn't think people burned books any more.”

In fact, the principal character of the story doesn't have to be lesbian, gay, or bisexual in order to generate complaints; simply the presence of LGBTQ characters, even secondary ones, is enough. Raina Telgemeier's Drama is a tremendously popular graphic novel that tells the story of the drama — both on and off stage — that middle schooler Callie and her friends encounter as they prepare for a school musical. But one of Callie's friends is open about being gay (at least among his friends) while another is questioning his sexuality — and when one of the boys has to step into a female role in the play, he kisses the play's male lead. As a result, Drama was one of the top 10 challenged books for 2014 for being "sexually explicit". However, as many parents point out, if it's not considered sexually explicit when the handsome prince kisses the princess at the end of a fairy tale, it's obvious that these complaints are not actually about the kiss, but about the sexuality of the characters.

If homosexuality and bisexuality are considered controversial, it's not surprising that books featuring transgender girls and boys have also been the target of would-be censors — especially given the national debate about transgender rights this year. Teen transgender activist Jazz Jennings is growing used to her writing being challenged; she co-authored a children's book, I Am Jazz (age 4 - 8) which explains what it means to be a transgender child. Jennings explains her transition in childhood in a simple, positive way, but challengers have called the book "inaccurate" and consider it inappropriate for the target age group. Jennings released a memoir this year, Being Jazz: My Life As A (Transgender) Teen for age 13 and up; it's already receiving its share of challenges, despite only being in print for a few months.

If homosexuality and bisexuality are considered controversial, it's not surprising that books featuring transgender girls and boys have also been the target of would-be censors — especially given the national debate about transgender rights this year. Teen transgender activist Jazz Jennings is growing used to her writing being challenged; she co-authored a children's book, I Am Jazz (age 4 - 8) which explains what it means to be a transgender child. Jennings explains her transition in childhood in a simple, positive way, but challengers have called the book "inaccurate" and consider it inappropriate for the target age group. Jennings released a memoir this year, Being Jazz: My Life As A (Transgender) Teen for age 13 and up; it's already receiving its share of challenges, despite only being in print for a few months.

Another book that tackles transgender issues, Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out (age 13 and up), also appears on the 2015 most challenged books list. This book, which features interviews of six transgender or gender-neutral teens and young adults, has been called anti-family and unsuitable for the age group; challengers have also protested its "offensive language" and what they deem "political" viewpoints expressed in its pages.

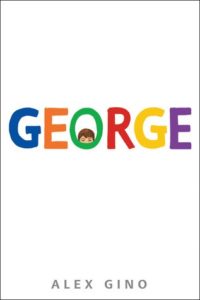

In 2016, George (age 9 - 12) joined the list of the Top Ten Most Challenged Books. George won both a Stonewall Award and a Lambda Literary Award for its depiction of a trans child coming out, particularly for author Alex Gino's clever use of pronouns: while the world interacts with George as a boy, the narrator refers to her with female pronouns, highlighting the conflict between external appearance and internal identity. However, administrators in several areas removed the book from shelves because of its portrayal of a transgender child and because "sexuality was not appropriate at elementary levels."

Hiding the Truth: Banned Non-Fiction

Bans relating to sexuality become particularly problematic when you’re looking at non-fiction, because they involve restricting access to facts that challengers consider immoral. These objections often have a religious basis, but not always: they can also come from a belief that access to this information will encourage sexual behaviors.

![cover[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/cover1-248x300.jpg) Robie H. Harris is the author of multiple sexuality-education books for all ages, including the classics It’s Not The Stork (age 4 - 7), It’s So Amazing (age 6 - 9), and It’s Perfectly Normal (age 10 and up), and the new series Let’s Talk About You And Me (age 3 - 7). Her earlier books have all spent time on challenged and banned lists for multiple reasons, mainly having to do with sexual content: they reference intercourse and show cartoon images of sexual anatomy, and books for older age groups discuss HIV, AIDS, and other sexually transmitted infections; sexual abuse and sexual assault; birth control, miscarriage, and abortion; and masturbation. They also depict a variety of families, and the presence of single-parent, homosexual, and even mixed-race families in her books have been cited in challenges.

Robie H. Harris is the author of multiple sexuality-education books for all ages, including the classics It’s Not The Stork (age 4 - 7), It’s So Amazing (age 6 - 9), and It’s Perfectly Normal (age 10 and up), and the new series Let’s Talk About You And Me (age 3 - 7). Her earlier books have all spent time on challenged and banned lists for multiple reasons, mainly having to do with sexual content: they reference intercourse and show cartoon images of sexual anatomy, and books for older age groups discuss HIV, AIDS, and other sexually transmitted infections; sexual abuse and sexual assault; birth control, miscarriage, and abortion; and masturbation. They also depict a variety of families, and the presence of single-parent, homosexual, and even mixed-race families in her books have been cited in challenges.

Harris said in an interview in 2006 that educators often tell her that if she removed some of these controversial topics her books would be used in their schools, but she responds that “I would personally do a disservice to the kids who read this book if I leave these things out. How can you...responsibly talk about sexual health without talking about all of these issues?”

Lynda Madaras, author of The What’s Happening to My Body? Book for Girls (age 9 to 15) and Ready, Set, Grow, its companion book for girls aged 8 - 12, also frequently receives challenges for the content of these books, as do her parallel books for boys. Although they are less explicit and detailed than Harris’ books, the illustrations of sexual anatomy, the medical descriptions, and the definitions of slang terminology have all been cited by critics. However, Madaras has also expressed her belief that communicating this information is crucial, especially when kids don’t feel that they can ask these questions of adults in their lives.

The Dangers of Censorship

It can make parents uncomfortable when they encounter violence, sex, racism, or religious questions in books for children. But at A Mighty Girl, we believe that children deserve to have the opportunity to explore these issues openly, with the support and assistance of parents and educators. Removing books that tackle these problems from the shelves does not eliminate a child’s need to learn about them; instead, it drives that need underground, where kids will seek what information they can glean from unreliable sources.

So the next time you encounter material that you’re worried about in a children’s book, sit down and read it with your child. Make sure she understands what’s being discussed, and talk about your own opinions and beliefs. That’s how you turn challenging words and ideas into positive opportunities for learning.

Additional Recommended Resources

- For more on Banned Books Week, check out the American Library Association’s page and their lists of Frequently Challenged Books.

- As a frequently challenged author, Judy Blume has her own page about censorship.

- Especially in the case of nonfiction books, banning books that provide accurate information can become an educational issue. Check out our section on Educational Access for stories that address the problem of being unable to access education and books.

- If you’re a parent who wants to read some of these challenged (and challenging!) books with your daughter, check out our Literacy / Book Clubs section for parenting books about fostering literacy and reading with your child — or, find out about creating your own Mighty Girl book club to read these and more great, girl-empowering books.

![1176340_696555130358581_1919643592_n[1]](https://www.amightygirl.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/1176340_696555130358581_1919643592_n1-e1379847237979.jpg)